Country Spotlight: Taiwan’s Digital Quarantine System

Student contribution

The following was written by Melyssa Eigen, J.D. Candidate at Harvard Law School, and Flora Wang, a 2020 J.D. Graduate of Harvard Law School and Assembly Student Fellow at the Berkman Klein Center, under the guidance of Professor Urs Gasser. This is the fourth installment in a series of briefing documents about COVID-19 apps in several countries around the world. Previous briefing documents cover Singapore, Switzerland, and Germany. [1]

An Overview

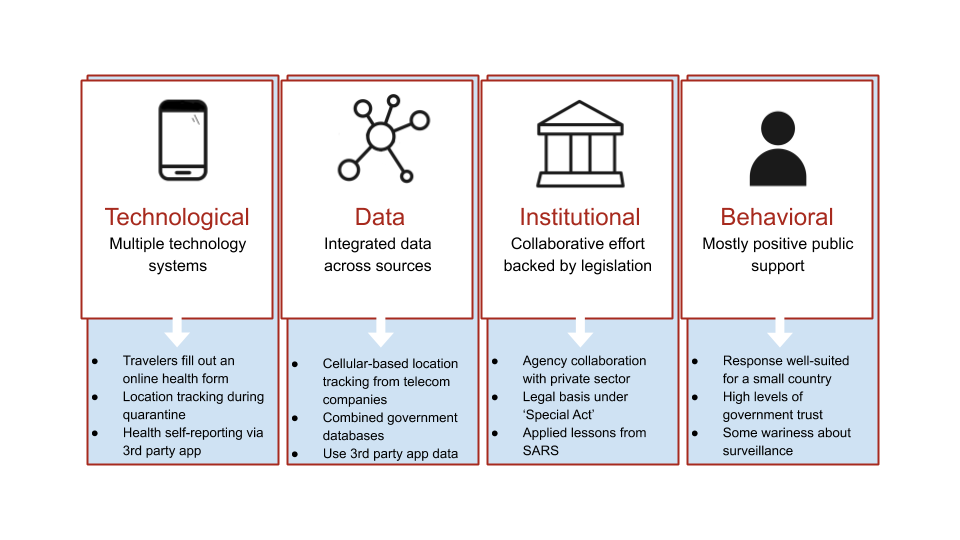

On January 20, 2020, the Taiwan Center for Disease Control (CDC) launched a comprehensive COVID-19 strategy by activating a Central Epidemic Command Center (CECC). Taiwan’s response includes a digital quarantine tracking system, which is managed by the CECC and applies to travelers arriving in Taiwan from overseas. The following provides insight into the technological, data, institutional and behavioral aspects to Taiwan’s quarantine system as well as some additional key factors of its response, most notably its implications on civil liberties in Taiwan.

Technological

Taiwan’s digital quarantine system is an online system which collects data from and tracks individuals undergoing a mandatory 14-day quarantine after entry. The system is mandatory for anyone arriving from overseas, with a few recently added exceptions for groups such as business travelers. Airlines require travelers, both citizens and foreign nationals, to scan a QR code that will direct them to fill out an online “health declaration form” before boarding their flights. This registration process “ensures faster immigration clearance for those with minimal risk” after landing in Taiwan. The system registers the user for a quarantine pass with the traveler’s information, passport number, and quarantine address. If a traveler signs up for the quarantine system with a Taiwanese SIM card prior to landing in Taiwan, they will receive a text from the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) with a link. After clicking the link, the passenger can access government issued quarantine documents, such as a home quarantine declaration certificate. The documents are password protected with the last six digits of the traveler’s passport. However, if the passenger did not register with a Taiwanese SIM card prior to entry, they must re-register with a Taiwanese number at the airport.

Travelers can choose to undergo quarantine at home or at a government approved quarantine hotel. The Taiwanese digital quarantine system tracks individuals during their quarantine period through the “Electronic Fence System,” which uses cell phone location data to ensure that travelers do not leave their quarantine location. If a traveler violates their quarantine by leaving their quarantine location, the government will issue an automated text message warning to their cell phone to notify them to return to their quarantine location, as well as to the relevant government authorities, ranging from the local police precinct and the local city government. Travelers are not permitted to turn off their phones or put their phone on airplane mode during their quarantine. The digital quarantine system sends automated SMS messages to individuals in home quarantine daily, and users can “directly reply to the messages to report their health conditions.”

In addition, the government has partnered with LINE and HTC to produce “LINE Bot,” also known as “Disease Containment Expert,” which sends daily SMS messages and monitors the health of individuals during home quarantine. Launched on Apr. 3, 2020, the LINE Bot helps monitor the user’s health during quarantine. Individuals can voluntarily choose to use this application to report their health status daily to the chatbot and receive information about disease prevention. While the digital quarantine technology is not seamless as there are still manual steps in the process, the potential for inaccuracy with cellular tracking and the potential for people to have multiple cell phones, the system’s overall comprehensiveness makes it effective.

Data

Taiwan has been able to effectively utilize big data in the fight against COVID-19 by collating data from telecommunications companies, pre-existing government databases and third party applications. Rather than using GPS tracking, the five major telecommunication companies in Taiwan work with the government to “triangulate the location of their cell phone relative to nearby cell towers.” Government officials claim that “only about 1% of alerts are false alarms.” Taiwan has a high rate of mobile phone usage, with one survey finding that 99% of Taiwanese people own at least one cell phone. The government claimed that although the Electronic Fence System is not as accurate as GPS tracking, it is less privacy invasive, and that this technology has drawn the interest of several other countries. Only the CECC is able to access the aggregated data from the Electronic Fence System. City officials are restricted to city-level information, and the police responding to quarantine alerts are only able to see an individual’s name, phone number and address. Fines for breaching quarantine can range from NT$10,000 (around USD $330) to a maximum penalty for serious violations at NT$1,000,000 (around USD $33,000).

Moreover, Taiwan has been able to effectively and quickly manage the pandemic by combining existing data from the National health Insurance Administration (NHIA) and the National Immigration Agency. The merger of such databases allowed the government to combine travel history with NHIA identification data, and also take advantage of the household registration system and foreigners’ entry card information. The government also granted “hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies in Taiwan...access to patients’ travel histories.”

The government has also partnered with third party applications to respond to the public’s concerns about COVID-19 and home quarantine. Apart from LINE Bot, the government has also partnered with Google. In May 2020, the CECC launched a bilingual Google Assistant chatbot which provides information to the public, including “introductory information on COVID-19, method of transmission, symptoms, epidemic status within other countries/regions and face mask stocking information in each pharmacy.”

Institutional

Under the CECC’s centralized command, Taiwan’s government agencies partnered with private entities to quickly respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to Taiwan’s experience with the SARS pandemic in 2003, the island was able to quickly coordinate a comprehensive response across agencies by re-activating the CECC. The CECC is housed under the CDC, which is an agency of the MOHW. The CECC directs intra-government collaboration, ranging from government institutions such as the NHIA, the Ministry of the Interior National Immigration Agency, and Executive Yuan's Department of Cyber Security. One example of public-private partnership is the National Communications Commission’s collaboration with the five leading telecommunication companies in Taiwan to establish the Electronic Fence System.

The CECC’s coordinating authority for quarantine and tracking comes from the Communicable Disease Control Act (“CDCA”), and the Special Act on COVID-19 Prevention, Relief and Restoration (“Special Act”). These two pieces of legislation provide the CECC “clear authorization to enforce any disease prevention measures it deems necessary.” In addition, the government states that although cell phone location data is protected by Taiwan’s Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) of 2015, tracking cell phones using the Electronic Fence System is “necessary” and that “telecom companies are ‘furthering the public interest’” in response to the global pandemic. Furthermore, the CECC issued guidelines for the third-party collection of personal data related to the pandemic in May 2020.

Behavioral

Taiwan’s response to COVID-19 has been successful to date, which is a product of the government’s preparation as well as the implementation of a strategy tailored to the Taiwanese population. Due to its close proximity to China and the frequency of travel across the Taiwan Strait, the island “was expected to have the second highest number of cases of.. COVID-19.” Yet, so far Taiwan has one of the lowest rates of COVID-19 transmission in the world, with less than 470 confirmed cases and seven deaths. Taiwan’s success can be explained by the following: First, as an island of an estimated 24 million people, it is easier for Taiwan to enact restrictions and monitor travellers than it would be with a more populous country. Second, the digital connectivity of the Taiwanese people, with 99% of the population using mobile devices, made it possible to enact cellular location tracking as an effective means to enforce quarantine. Third, a general acceptance and trust in the government has also helped to make the response effective -- according to a poll from early April 2020, the public rated the government at 84/100 for its COVID-19 response, which perhaps correlates with the public’s overall compliance with the quarantine system -- as of mid-March 2020, there were only an estimated 70 quarantine violators who had been fined. Given that Taiwanese people are typically sensitive to data protection, the support may seem surprising, but people have been more accepting due to the greater “necessity for the public good” in combating the virus and also due to the “openness of the government’s communications.” One returning student described it as “wanting to do their part” in protecting the community. It is also possible that there is general support because the public does not understand how the technology works. However, not all reactions have been positive with respect to the high level of surveillance enacted by the government -- one citizen called it “creepy” and felt that she was “treated like a prisoner” during her quarantine. These concerns over government surveillance and intrusion of civil liberties potentially explains other countries’ hesitance in using location data in their responses.

What’s interesting about Taiwan’s digital response?

Civil Liberties

As the government is seemingly prioritizing efficiency and flexibility over privacy in its response to the pandemic, this strategy raises numerous unanswered privacy and civil liberties concerns. Given Taiwan’s relatively recent evolution from martial law to democracy, “Taiwan’s civil society is particularly sensitive to potential overreach over its hard-earned civil liberties during the pandemic.” As mentioned above, the CDCA confers the government broad power to conduct digital quarantine tracking, but “it also invites questions about potential abuse” and privacy. Even though “the government has said the tracking system will be discontinued after the pandemic passes and all stored personal data will be deleted at that time,” government communications about privacy lack transparency and clarity. Information about the storage, retention and deletion of the personal data gathered by these systems is not listed in the Entry Quarantine System. For example, it is unclear to a user filling out the Entry Quarantine System form that the cell phone tracking begins once the user arrives in Taiwan. Furthermore, although the government claims that the tracking system only applies to those undergoing home quarantine, the online form does not clearly describe any protections for privacy and user data when travelers enter their information into the system. The lack of transparency over the use of data in the system is troubling.

Moreover, there are additional vulnerabilities and unanswered questions related to the digital tools used by Taiwan to combat the pandemic. Although the government claims that cellular location tracking ends after the 14-day quarantine, it is unclear whether it stops immediately or if there is a lag. As many parties have access to a user’s location information during this time, which already seems like more parties than the “need to know” authorization designated by the PDPA, this could be concerning. Furthemore, the consolidation of government databases raises cybersecurity risks. There are cybersecurity risks in having personal data in a single location, which has been highlighted by recent hacking attempts that targeted the Taiwanese government. There has been little transparency or clarity about who at “hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies” is given access, and for how long. Similarly, there is little transparency for third party applications like LINE Bot. There is almost no publicly available information about how long data is stored, who has access to it, and if it can be sold. The Taiwanese government should provide more information on these topics in order to respect its citizens’ civil liberties.

Furthermore, the Special Act grants the government expansive power to publicize personal information about individuals. Article 8 stipulates that the CECC could potentially “record videos or photographs of the individual’s violation, publish their personal data, or conduct other necessary disease prevention measures or actions.” The Act states that “the personal data...shall be processed in accordance with related regulations for personal data protection after the end of the pandemic.” The Act implicates several civil liberties concerns. First, while the Special Act is set to expire on June 20, 2021, the Act could be renewed indefinitely, or be renewed with the removal of existing safeguards. Second, although the government has so far anonymized the names of individuals whose information have been published, a case involving the government’s release of location data of an undocumented worker who had COVID-19 raises questions about the criteria the CECC uses in determining whose data to publish. Third, Taiwan should ensure that any information released safeguards the identity and privacy of the individual from being easily recognized, even if the government releases their location history, photos, or other personal information.

Physical Enforcement

One defining and interesting aspect of Taiwan’s quarantine system is the enforcement element. While many aspects to the government’s response are digital, the enforcement is ultimately an in-person endeavor. Once the local police are alerted by the telecom system that a quarantined individual has left their quarantine location, the police are ultimately responsible for following-up with them in person. For example, one person recounted waking up to the police knocking on his door when his phone was turned off for an hour. “They’ll find you and they’ll fine you,” said the National Communications Commission, who helped set up the location tracking system. In conjunction with the Electronic Fence System, the government is also using the M-Police System, a cloud-based database created in 2007 that lists people under quarantine orders. The police can access this database, and go out and check for any of these individuals at public places to catch quarantine violators. For instance, if someone were to turn off their phone so that they could leave their quarantine location undetected, the police could still find and penalize them. In one example of this technology, the police were patrolling the area for violators and used the M-Police database to verify that an individual, who was out clubbing, was actually supposed to be in quarantine. While there is still room for error given the manual aspect of the system, the location tracking system coupled with the M-Police database would make it difficult for an individual to breach their quarantine undetected.

Comprehensive Economic & Digital Response

Citizens of Taiwan ordered into quarantine are given financial assistance to help them cope with the cost of being quarantined. For example, the Taiwanese government has acknowledged the potential financial burden of complying with mandatory quarantine by offering subsidies for both quarantine hotels, for those who are required to stay in them as opposed to quarantining at home, and quarantine taxis. However, only Taiwanese citizens are eligible for the subsidies. Further, the government was also cost-conscious by not investing resources in a separate Bluetooth contact tracing app. Instead, Taiwan relies on already existing resources, like cell towers and government databases, as well as on the voluntary participation of the public, like through an online “brainstorming” platform called vTaiwan. Additionally, Taiwan also integrated their economic and digital response by creating an e-ordering system for masks as well as a database for mask-rationing. Lastly, the government has exhibited a comprehensive economic plan with their “triple stimulus” program, which gives people NT$3000 (around USD $100) worth of vouchers when they buy NT$1000 (around USD $35) in vouchers that can be used in a range of commercial areas. By bolstering their digital response with financial incentives and subsidies, Taiwan can hopefully continue to maintain an effective response to COVID-19.

[1] Thank you to Gregory Nojeim at the Center for Democracy & Technology for your input on this topic.